Archive for the ‘Food politics’ Category

Being in the sustainable food business in a small town and rural neighborhood is both an inspiration and a challenge. One of the vendors from our local farmers’ market was banned a few weeks ago, ostensibly because they were not “local.” Of course, the stories surrounding the incident vary, based on who you ask, but the basic thread is that the vendor did not “follow the rules” and was from <gasp> Duarte. The contraband in question was stone fruit; apricots, peaches, nectarines, cherries, you know, the hard stuff! A vendor friend noted that they had UPC stickers on their fruit, a sure sign of the conventional commoditized food system; surely not a sign of a small, artisan producer? I reflect on the bar coded UPC’s on my own olive oil bottles, a similar litmus test? Many of us as small producers must court multiple sales channels in order to survive. Grocery equals UPC codes; non-negotiable in their world. Even my local customers prefer to purchase our olive oil in their local grocery store, hence the dance with the devil. Without UPC’s and a distributor, the grocery channel is virtually closed to the small producer.

We define local, here on the Mendocino Coast, as somewhere between 100 and 150 miles circumference. This allows us the grains and beans cultivated in the central valley, while still preserving the intrinsic relationship between farmer and customer. My sister lives in the suburbs of Washington, DC, and in her world, local is within 800 miles circumference. In the urban mid-Atlantic, small farms are harder to find. We are spoiled here in California, where farmers live within driving distance of urban markets. Many of us take for granted the cornucopia of regional produce displayed at our local farmers’ markets. Here in Mendocino County, this bounty is limited to the months of May through October, when the certified markets are active. If we wish to partake in seasonal winter vegetables, locally produced, a CSA is often our only option. We are fortunate here in Fort Bragg to have a relationship with a year-around CSA farm. Not everyone is so lucky. In fact, one of the reasons that the disputed produce vendor was even in our local market was to supply fresh items in winter not available in our more severe climate zone.

A successful farmers’ market is a vibrant and diverse market. Thus defines the dilemma. Do we limit the market to only local vendors, and, for that matter, one vendor per commodity? While an ideal situation for the producer, this limits the customers’ choices, and, as a result, their patronage of the market. More choices = more customers, and more customers = higher sales for market vendors. Somehow this equation does not hold true with our local market association. The “rules” supersede the customer. But, what is a market without a customer? By definition, a market exists when a seller and a buyer agree on an exchange for a particular commodity. Without these components, a market does not technically exist. Our lesson; make the maximum variety of commodities available to the consumer. The market will sustain itself. If the commodity has no value to the customer, then the market, or the vendor, will fail.

Open markets promote open minds. We must trust the market forces to drive the equilibrium. If a commodity has no demand, and therefore no value, the market will demonstrate to the vendor that they cannot sustain their participation. Almost Darwinian, those who succeed have the characteristics of success. If your product has value, it will be reflected by the customer as increased sales. No need for oversight, no need for regulation, the force of the market prevails. If there is a buyer and a seller, there is a market. It is not about the random regulatory boundaries exercised by an outside entity. We must reflect on this basic principle of commerce and embrace the essence of its power.

No matter how you define “local” or “regional.” It is about buyers mated with sellers exchanging the value of a given commodity. This is the essence of the freedom of choice characterized in a market economy.

To one customer, located somewhere west of the Mississippi, but where olives are not cultivated, my product might be considered “local.” Yet in a market less than 200 miles away, where olives trees are more common, it is disqualified on the same criteria. It is not about the random geographical boundaries. It is about access to clean, fair and healthy foods. Something we Californians take for granted, but perhaps should not. Every producer is an artisan of sort; and is it our privilege to categorize and judge, or should we simply fulfill our role as buyer, and let our choices speak the truth instead?

Post by Julia Conway on July 21st, 2009

Tags: Food politics

Posted in Country life, Local food, Mendocino, Olive oil, Seasonal food, Slow Food, Sustainability

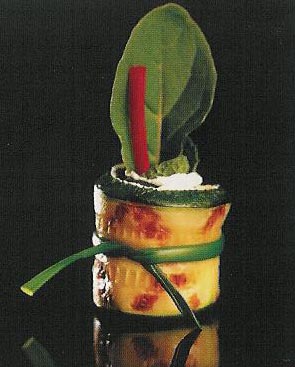

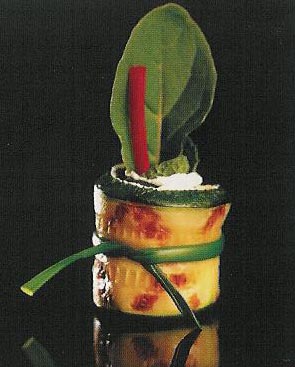

What is the world coming to, where certain festive food preparations are so intricate and elaborate that our guests are afraid to sink their teeth into them, for fear they will disturb a masterwork of fine art? A trade publication aimed at caterers arrives in the mailbox every month, laden with glamorous photos of the latest and greatest trends in celebration foodstuffs. Many of these companies must have legions of prep cooks spending days, even weeks, manipulating food into incredible shapes, forms and colors. The novelty of it all is an obvious draw, but somehow, behind this eye-catching façade, the food looks somehow tortured. It is as if it is screaming to get out, begging to take its original form.

The food scene today is a mirror of affluent society. The public persona is far larger than life. Everything is engineered to be exceptional, flawless, or at least appearing to be, morphed into a garish sameness. Our homes, our cars, even our bodies and our faces are rearranged to fit the girdle of current fashion. The same is true of our food. Food has become a lifestyle accessory. Magazines urge you to be the first on you block to try the latest restaurant, to prepare the ingredient of the moment, to host the party of the decade. It is as if we are all supposed to have an army of food stylists in our pantries, turning out dishes that would make Martha Stewart green with envy! Chefs are the new stars, with televisions shows, signature endorsements, fan clubs and even sporting events. Leisure time is spent pursuing the latest darlings of the food and wine publicity machine. As a chef and food writer, I can’t help but wonder which item from my compost bin will become the new ingredient du jour. This spring it is fava bean leaves, yes, fava bean leaves! Now how am I going to augment the nitrogen in my garden beds if my fava bean sprouts are going into the salad rather than being hoed back into the soil? My gardening catalogs call it “green manure” and I am sure that this label is not going to be showing up on restaurant and catering menus any time soon! Nor am I saying that these little green tidbits are not delicious in their own right, but what angst-ridden chef, attempting to create yet another new menu extravaganza came up with this one? I read today that Thomas Keller of the French Laundry never repeats an ingredient more than once in a menu, with the exception “…of course…” of such luxury staples as the truffles, lobster, caviar and foie gras on which his restaurant’s reputation is built. Try that at home? I don’t think so.

Below the surface, economic rumblings are echoing across continents and oceans. Can we continue to feast on the latest and greatest while Rome (or Wall Street) burns? It has been portended that this recession may reset the sensibilities of our nation and the world, ending the mad rush of unconscious consumerism and waste. In this spirit, I would like to challenge the food world to go back to its roots as well. I would like to call for an end to food as entertainment; and a return to food as nourishment and pleasure. I would love to see one of these glossy lifestyle magazines speak of entertaining and eating for personal enjoyment, rather than as an outward manifestation of an idealized life. To that end, I have chosen to take the path less trodden, breaking my own way as if wandering across a meadow full of spring grass. The menus I will develop for this summer’s catering season will reflect food for food’s sake. Rather than steaming, pureeing, freeze-drying and reforming a carrot into a sheet of paper in which to wrap carrot tops, I will trim them and roast them whole with a sprinkling of warm spices reminiscent of North Africa. Rather than cutting my potatoes into perfect ¼” dice and poaching them in goat butter with fennel fronds, I will toss them, unpeeled, with new olive oil and kosher salt, and bake them until their skins are crisp and the insides are creamy, splitting them open to absorb a light dressing of mustard vinaigrette. Instead of braising my carefully turned artichokes for hours in lobster stock and mashing them through a drum sieve with mascarpone to stuff ravioli, I will steam them, halve them and sear them on a griddle until caramelized and sweet. Spring onions and leeks will not be transformed into thin green ribbons with which to wrap a terrine of foie gras, but will actually be grilled and dipped in a spicy, smoky Romesco sauce, to be eaten whole.

The menus themselves will be patterned after what the Italians call “la cucina povera,” the poor foods. These are not the recipes of the de Medicis and the Renaissance, but the recipes of the villages, the farms, and the fields of the Mediterranean. In keeping with the economic times, these menus will also be more affordable and accessible. In order to understand our future, we must understand our past. Often the simplest preparations are the most flavorful.

When I brought the heaping platters of carrots and onions to an event recently, eyebrows were raised and heads wagged. Yet when the wrappings were removed, the aroma of roasted vegetables and savory spices filled the room. The guests’ first bites were tentative, almost afraid to believe that something so simple could possibly be satisfying, much less exciting. Yet one by one, their faces lit up. Smiles stretched and eyes rolled up in pure bliss. Lips were licked and words were offered up like “wow” and “incredible.” The food transformed those who ate it from bystanders to participants. Fingers were finding their way into people’s mouths as they wiped the last specks of sauce from their plates. A small crowd gathered around the platters, not dispersing until the last morsel was gone. The beauty of these foods were in their honest simplicity, recognizable, and yet in no way mundane. Somewhere, in the back of people’s minds, memories were awakened; a warm tomato eaten while standing in the garden, a slice of freshly baked bread, still hot from the oven, the first bites of the season’s earliest sweet corn. Basic foods, honest foods, satisfying and nurturing foods and, if we are honest, the foods we remember when all else fades away. These are the foods we can choose to prepare and to enjoy, and most of all, to share.

Post by Julia Conway on April 11th, 2009

Tags: Food politics

Posted in Catering, Food Network, Slow Food

|

|